It was probably Rauf’s second month in school when I saw it with my own eyes.

It was after school. He wanted to stay back a little longer to play at the playground. I stood to the side, watching him.

Then, out of nowhere, a boy appeared behind him. He picked Rauf up and shoved him to the ground. He banged his head. Pulled his jacket. Shoved him again. Then he clenched his fist, ready to punch Rauf in the face. I yelled, “HEY.”

He froze. He hadn’t realised I was there. I asked where his parents were. He pretended not to speak English. I was furious — because that wasn’t play. That wasn’t kids being kids.

I asked where his guardian was again. He looked at me, said “adios”, and ran off. This boy spoke French and he was Rauf’s classmate.

I was deeply disturbed. It was unprovoked. I wrote to his teacher. Her response? “Rauf is rough in school too, so it’s not a big deal.”

Fine.

Things were quiet for a while. Then, two or three months before the academic year ended, I received an email from Rauf’s class teacher. She wanted to talk.

I didn’t think much of it. When I went in, she said Rauf was showing signs of “having difficulty regulating.” I remember thinking, what the hell does that even mean?

We knew Rauf got over-excited around other kids. He was an only child. There were only three of us at home. He hadn’t had many chances to burn energy or socialise before school. It didn’t feel alarming. We did notice one thing — he started fidgeting more. Twirling his hair, constantly. But that was it.

Then the emails started coming.

“Rauf did this.”

“Rauf said that.”

“Rauf disrupted this.”

Soon, it wasn’t just emails. It was confrontations during pick-up. More public, hurried and uncomfortable.

I found myself interrogating Rauf every single day after school. Trying to piece together what really happened. Trying to make sense of it all. We added more rules at home. More structure. More restrictions. I convinced myself this was how you helped a child “regulate.” It was a lot for Rauf too.

Until two incidents made me snap. I remember thinking: Enough. I don’t know what on earth I’m supposed to do anymore.

The breaking point was when the teacher told me Rauf had threatened to hurt his classmates. I was open to listen what happened but the way it was shared with me was more of a statement then trying to figure out together how to address this concern. That didn’t sit right with me.

Thankfully, one of the parents of the children involved went home and actually asked his son what happened. The truth came out quickly: the kids Rauf supposedly threatened were the ones who had threatened him first.

Of course, Rauf shouldn’t have responded with words of violence — but I was appalled that the teacher was so confident in pinning him as the problem without investigating further.

Realistically, wouldn’t you look deeper if something violent was said among eight-year-olds?

That parent confronted the teacher for her poor due diligence. I was grateful — but it also made me realise something else: Rauf’s learning environment felt messy, and I didn’t know how to protect him in it.

All the complaints came from one teacher. Just one.

Academically, Rauf was doing well. Socially, he was thriving.

So why were playdates and birthday invitations piling up if he was supposedly so problematic? Why had no other parent ever reached out to me directly?

Something was off.

It got to a point where I was terrified of school pick-ups. When Joe was around, he would fetch Rauf. I’d wait in the car.

Deep down, I knew there wasn’t anything “wrong” with my child — but the constant complaints made me doubt everything.

There were weeks when Rauf came home crying, telling me that one or two kids were being mean to him in class. I told him to inform his teacher. “I did. But she never listens. So I don’t tell her anymore.”

Then came the day he came home completely broken. He cried uncontrollably. He said he couldn’t take the meanness anymore. I informed the teacher.

She looked me in the eye and said, “It all starts with Rauf. It’s his fault.”

Later, one of the parents of those same kids came up to me and said “The teacher told me what happened. Even she said it was Rauf.”

That day, I felt like I had failed — not just as a mother, but as a human being. Even without working full-time, I felt like I wasn’t enough for my son.

That evening, Rauf and I stopped by the grocery store.

He asked if he could get some chocolate. I said yes. He hugged me and said thank you. Then he picked up the trolley basket and said, “It’s okay, mummy. I’ll push it for you.” I didn’t say a word while we shopped. I just felt numb.

In the car, he insisted I try his chocolate. He broke it in half and handed it to me, saying it was delicious. I took a bite.

Then he asked a question that changed everything “Mummy, where are we going after the Netherlands?”

I explained that Daddy might be posted somewhere else, but we might not be able to follow. I told him how hard it was for me to find work, how we’d probably need to go back to Malaysia and daddy has to go someplace else.

He went quiet. Completely silent.

After a while, he said,

“Mummy, I want you, Daddy and me to be together. So I have an idea.”

“What is it?” I asked.

“If we move to another place… you can work as a babysitter.”

I could my brain asking ‘Huh? of all things? I can’t even care for your properly’

“Because you’re a good mum. And you’re good with children. After you take care of other kids, you can take care of me after school.”

After months of doubting myself, of being told — directly and indirectly — that something was wrong with my child and maybe with my parenting, it took my eight-year-old to remind me that I was just a mum trying her best.

And that was enough for him.

That was the moment the switch was clicked.

If someone was so adamant that something was wrong with my child, fine. But I would find out myself. We sought professional help. We screened for learning disabilities, ADHD, even autism. After thorough assessments — nothing. He was fine.

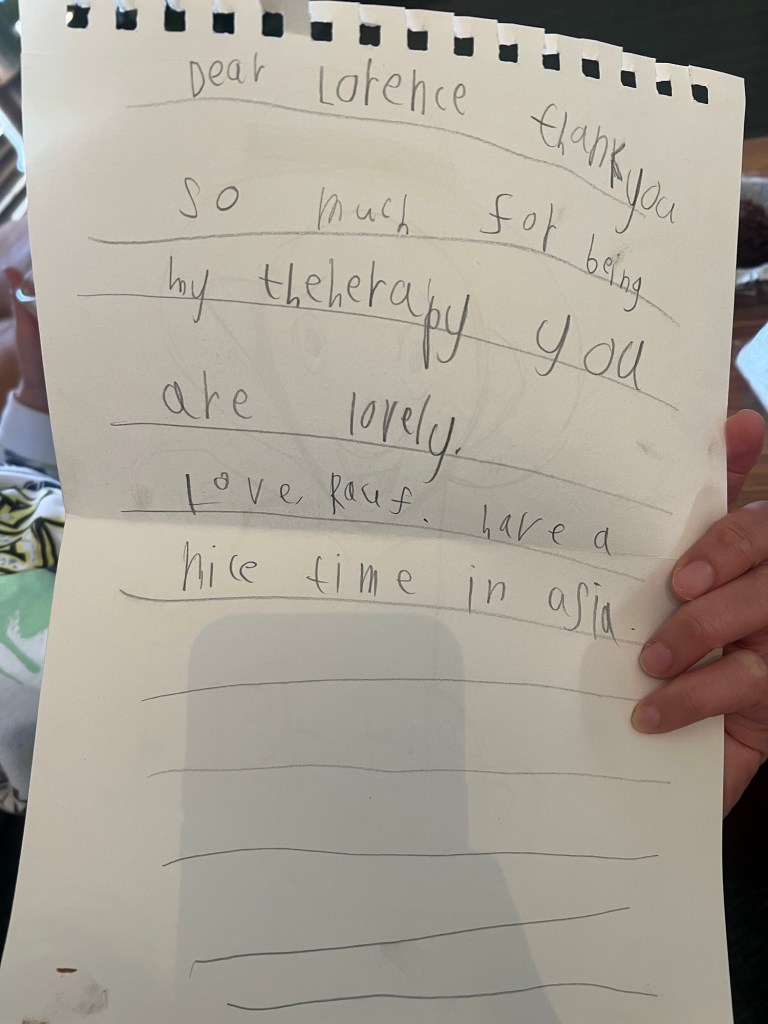

Because of the fidgeting, we were referred to an occupational therapist. Her name was Lorence and she was an angel. She explained that Rauf was simply a normal, energetic boy who got over-excited and didn’t yet know how to channel that energy. That was it.

He was loud because he was happy. And yet, somewhere along the way, that had been mistaken for something broken.

Therapy continued until we left the Netherlands. It helped us understand how Rauf experienced excitement — how it built up in his chest, how it overwhelmed him, how the fidgeting was just his body trying to cope.

And that boy from the playground?

Not that I take pleasure on this, but the following academic year, there were multiple reports about his bullying behaviour. He was the same child who hit Rauf’s with a big stick on Halloween. The same child who attacked him again on the playground — this time, thankfully, witnessed by a teacher.

Sometimes I wonder what might have happened if my concerns had been taken seriously earlier.

Maybe a few children wouldn’t have been hurt.

Maybe some wouldn’t have been so scared to go to school.

If it wasn’t for Rauf, I wouldn’t have realised how important it is to listen to feedback — but filter it. It is important to stay open — but trust your instincts. And never forget that loud, excited, joyful children don’t need fixing. Sometimes, they just need someone to truly listen.